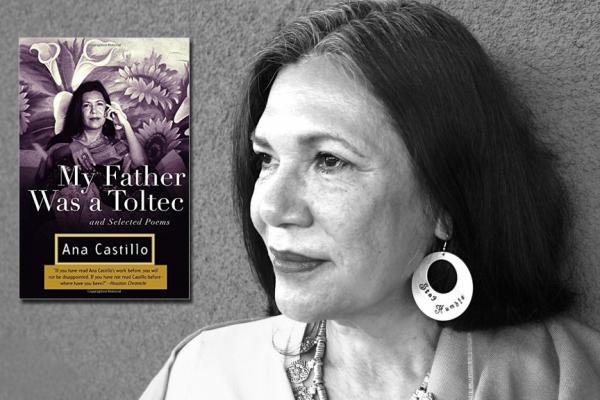

Electra in Ana Castillo’s ‘My Father was a Toltec’

(Part I)

“Chicago … shaped me into the kind of writer I have become. Multiple ethnic presences … prepared me for realizing that the world is not simply black and white or mostly brown. My first 20 years of life were spent around Taylor street” (Ana Castillo in Greg Holden, Literary Chicago. Chicago, Lake Claremont Press, 2001: 87)

Introduction

In a previous article on Ana Castillo’s work,I pointed to the greatest Chicago insight the author provides us in The Mixquihuala Letters, when Teresa comments on the growing awareness of ethnic and also feminist concerns stirred by the civil rights confrontations most directly expressed in the events between 1976 and 1978 in the Windy City. That perspective informs the preface and introduction to the reprinting of Castillo’s third book, My Father was a Toltec, a collection of poems which, by dealing with her own childhood, adolescence and coming into early womanhood, in many ways makes the collection stand as her own however truncated equivalent to Sandra Cisneros’ Mango Street text or the opening section of My Wicked, Wicked Ways. So in her introduction, Castillo tells us,

In the early seventies, the fires of the Latino Movement burned through the Midwest. In Chicago, much of barrio youth was ignited and became caught up in its unprecedented spirit. There were rallies at City Hall and conferences and similar calls for attention to the concerns of the city’s large Latino population. I was attending a girls’ secretarial high school. Once I graduated, the hope, given my family and background, was that I could find an office job. Something clean and out of the factory. But instead, the flames had reached me, licked my ankles and calves and set me ablaze and I now saw myself not as one more Mexican in the multitude but part of a major historical shift (Castillo, Introduction to My Father was a Toltec and Selected Poems [New York: Anchor 2004]: xxii-xxiii)

These words are the clearest articulation I have found about the central concern of at least the first phase of my overall study of Chicano writing in Mexican Chicago: the explosive Latino emergence in the Midwest and above all Chicago exactly in the period she specifies. The words are especially poignant when we consider Ana’s emergence as the erotic iconoclastic writer who rose out of her working class neighborhood to become a significant player in the ethnic and gender wars to mark the decades which followed.

Castillo started with a powerful passion for art and writing, but her life expectations were such that she attended secretarial school and community college before attending one of the least prestigious centers of higher education in her home city. Interestingly too, Castillo speaks of the rejection of her work as a working class Latina visual artist which channeled her burgeoning representational drive toward the written word. True, she had been stringing out lines of verse on yellow pads since her earliest years. Still, as more than one poem makes clear, it would be hard for her to develop as a writer if only because she felt her working class education and her English to be stunted. But class, ethnic and gender wounds discouraged her from pursuing her work as a painter from the time she graduated with a B.A. in art; and even though she felt limited, her creative drive compelled her to pursue and develop as a writer.

The effect of Chicago on Castillo’s creativity was such that at least some of her poems and novels (above all, Sapagonia, Peel My love like an Onion and Give it to Me) provide us with oblique and fictionalized, but suggestive windows onto the social and political realities of the city and its Latino world in the 1970s and beyond.

Here, leaving the novels and other texts in the background, I wish to explore the core of her youthful Chicago experience as it emerges in My Father Was a Toltec. Before I do so, however, a qualification is in order. I will not here seek to examine all the poems which appear in My Father was a Toltec and Other Poems. I’ve already dealt with many of the other poems in the above mentioned article, which focuses on her first full collection, Women are not Roses. However, even the ones included that were not in that earlier book, while providing a broader view of Castillo’s work, detract from the relative unity achieved by Toltec in and of itself as it was first published in 1988. So we’ll stick with that first version and trace its binding dynamic and enigmas—her relation to her father and the extension of that relation into her adult life.

In this light it is important to see how this text differs from several of her other creative works where her concern for the hereness, nearness and newness of life seem to overwhelm any deep historicizing drive. Such is not true in her essayistic writing and editing where general and cultural history, and above all Latino history are projected in an effort to explain the emergence, for example of the “Hispanic condition” and its career in the so-called New World. Castillo explored the roots of Chicana feminism in her co-translation of the epochal collection, This Bridge Called My Back; she went on to produce a whole volume on the woman figure seemingly furthest from her temperament—la Virgen de Guadalupe; she then explored the roots of Hispanic gender differentiation and sexism in the patterns and attitudes she identified with Marakesh in her virtual feminist manifesto, Xicanisma.

However, in her fiction and two other volumes of poetry, Castillo is usually too much focused on the present-day consequences of the past to focus too decisively or nostalgically on the past itself. It is only her ambivalent relation to her father that seems to overcome her focus on immediacy and set her off into a look at her own adolescence in relation to a simultaneous look at the Mexican synthesis of past processes and the importance of these processes on the recent Chicano past and on the present and future as well. This she accomplishes by playing out the implications of her father’s membership in a southside gang called the Toltecs, and this in relation to his role as Mexican husband, lover, father and indeed questionable, if decisive role model for the daughter who would become an aggressive, feisty and risk-taking writer.

Very conveniently for the daughter, the word Toltec conjures up not only the rough life she experienced as a Taylor Street girl, but also the Aztec and then Castillan-dominated Mexican world in which the Toltecs were one of the foundational Mexican indigenous groups that preceded, influenced and then fought against the hegemonic and ruthless Aztecs, even signing on with the Spaniards against them, only to be subjugated first by the Spanish and then, after 1848, by the Yanquis to the north as well. It is no accident that Castillo identifies to this day as her father’s daughter, “la tolteca,” that she half-jokingly places herself as a member of the Chicago Toltec tribe and dedicates the re-issuing of her Toltec volume, to “los y las Toltecas—del pasado, presente y porvenir (vii) and then, on her Acknowledgements page, writes “In memory of the Toltec, 1933-1990.” Her preface to the reissued volume has more to tell us about this Toltec theme, but I would point most to some of the things she says on the last pages of her preface—that first of all the modern Chicago Toltecs “had a heritage to claim. Departing from the Toltecs, however, and the ambition of youth to be brave and defiant, they didn’t have much in common with the original Toltecs. But I must add, in many ways, neither did the Aztecs.”

“I am holding on with some astonishment to how this modest tribute and meditation has spoken to others daughters (and sons) of Toltecs (i.e. descendents of great mythical tribes throughout the world),” she notes. “Their endurance—and mine—keeps me smiling in my heart. I hope our forefathers would be proud to know we claim them.” And she closes by saying, “I’ve never forgotten that my father was a Toltec.” (xix).

The introduction is fascinating not only by placing the poems selected in the context of the explosions of conscience and action in the 1970s but for all she has to tell us about her development as a cultural activist finding her voice as she begins to separate from the male-centered groups which were so important to her initial cultural work and starts to find her own way as performance artist (before the term had been elaborated) and writer.

But what is most centrally striking about this text and most fully realized in Part I is the unique, compulsive focus on her relationship with her Toltec gang father and his long-suffering wife. If anything, one might wish Castillo had given us several more poems in this section. Certainly, given her introduction, but above all given her recent Black Dove: Mamá, Mi’jo, and Me (2016) where she provides a much more detailed and mother-centered view of her growing up, involving all kinds of experiences (of the intense poverty she lived both in Chicago and Mexico City, of barrio fears and frustrations, etc.) she surely had the experiential basis for a much richer body of poems. However, it is true that the broader panorama might have diluted the central driving narrative which she understood to be the crucial motor of her move in and out of adolescence, a narrative which poses a variant of what Jungians, for example, have examined under the guise of the so-called Electra complex, wherein the child’s development is shaped by her fixation on her father in rivalry with the mother. This is a fixation whose variants have been explored in Sylvia Plath’s Daddy poem, Anaïs Nin Incest, and (to reference at least one Chicana writer crucial for Castillo), Cherrié Moraga’s Loving in the War Years. It is a fixation which in her own variant Castillo must somehow sublimate and transcend if she is to build a life for herself at all.

In this regard, outside of the psychoanalytical questions, I would point to one useful book which most of the few of us who even read about Mexican or Latino Chicago have generally ignored and forgotten, Ruth Horowitz’s Honor and the American Dream (Rutgers: 1983), which more than any other text focuses on Pilsen Mexican gang participation and its effect on the children of gang members, in the 1960s, just some years after Castillo’s own time as a child.

I. Tracing the Electra Story in The Toltec (My Father was a Toltec, Part I)

Once we grasp Part I’s Electra inner drive and focus, we can see where the poems may included play given roles in the telling, and where other poems in subsequent sections apparently more distant from the core structure may also find at least some points of illumination and relationship. The story in question is of a girl fascinated and embittered by her father who is both the leader and betrayer of her household world and clan—a figure she worships, admires, disapproves of and must finally overcome if she is to have a life at all. In effect, she is an Electra (and a key poem is called “Electra Currents”) who must kill off the murderer of her father. But the murderer of her father is not her mother and certainly not her uncle, but he himself who she the daughter, as in the myth and in spite of all, loves and whose death she must both prevent, and ultimately bring about. In a word the one she enlists to carry out a horrific but necessary killing is not some Orestes brother, but again, she herself, who will do so with the help of all her lovers, male and eventually, female as well. For if she cannot somehow kill off or make her peace with her father she cannot fully emerge as Ana Castillo. And if she cannot be Ana Castillo, what is the point of her life after all?

Let’s follow Castillo’s own logic, with a short picture of her father, his gang affiliation, his turf fights with the Irish and others, and the complicity of the poet’s mother in his world.

The Toltec

My father was a Toltec.

Everyone knows he was bad.

Kicked the Irish-boys-from-Bridgeport’s

ass. Once went down to South Chicago

to stick someone

got chased to the hood

running through the gangway

swish of blade in his back

the emblemed jacket split in half.

Next morning, Mami

threw it away.

Ana/Electra indeed arrives as a virtual nothing, a hopeless girl—an accident or miscarriage, laying her nothingness at the door of her Toltec Agamemnon father, one who doesn’t go off to the Trojan or Toltec war but just goes down the street to a local bar:

Electra Currents

Llegué a tu mundo

sin invitación,

sin esperanza

me nombraste por

una canción.

Te fuiste

a emborrachar.

So, unwelcomed into her father’s world, our young girl, now in school, reads of Sally and Tim, another Jill and Jack, and their red wagon on a sunny lawn with driveway so unlike the Taylor Street world she knew. Here, nothing depended on William Carlos Williams’ red wheelbarrow (a key trope from the work of one of the greatest U.S.—if half-Puerto Rican—poets) let alone on a red wagon, but on whether Father came home and with the money he hopefully hasn’t spent in a bar or on a woman to buy fuel for the cans that could be carted in that wagon (red or not) to heat a cold flat where he lives with wife and daughter.

Red Wagons

In grammar school primers

the red wagon

was for children

pulled along

past lawns on a sunny day.

Father drove into

the driveway. “Look,

Father, look!”

Silly Sally pulled Tim

on the red wagon.

Out of school,

the red wagon carried

kerosene cans

to heat the flat.

Father pulled it to the gas

station

when he was home

and if there was money.

If not, children went to bed

in silly coats

silly socks; in the morning

were already dressed

for school.

We see here the emergence of the feisty poet in meditation, focused most, it would seem, on the clothes involved in her father’s and then her own private and public poverty life. First comes the passive relation to clothing, as the Electra drama first set up in “Electra Currents” deepens in a poem young Latina students of mine have always relished, though with some bitterness—one in which mother and daughter act like Jean Genet’s Maids (only not two sisters, but mother and daughter, acting like complicit servants), preparing the clothes not of their lady but of their lord, for a night on the town:

Saturdays

Because she worked all week

away from home, gone from 5 to 5,

Saturdays she did the laundry,

pulled the wringer machine

to the kitchen sink, and hung

the clothes out on the line.

At night, we took it down and ironed.

Mine were his handkerchiefs and

boxer shorts. She did his work

pants (never worn on the street)

and shirts, pressed the collars

and cuffs, just so—

as he bathed,

donned the tailor-made silk suit

bought on her credit, had her

adjust the tie.

“How do I look?”

“Bien,” went on ironing.

That’s why he married her, a Mexican

woman, like his mother, not like

they were in Chicago, not like

the one he was going out to meet.

It is in the context of Mexican female acquiescence that the Ana Castillo we know is born and comes to be—again in the context of clothes, as in the case of Luis Valdez’s pachucas of an earlier moment.

The Suede Coat

Although

Mother would never allow

a girl of fourteen to wear

the things you brought

from where you wouldn’t say—

the narrow skirts with high slits

glimpsed the thigh—

they fit your daughter of delicate

hips.

And she wore them on the sly.

To whom did the suede coat with

fur collar belong?

The women in my family

have always been polite

or too ashamed to ask.

You never told, of course,

what we of course knew.

Some years later the new aggressive Ana is a tough high school girl, dealing with her Italian rivals, as her father had dealt with the Irish, in THE classic poem of Chicana-Italian American confrontation (in the midst of many romances, scandals, inter-marriages and the like):

Dirty Mexican

“Dirty Mexican, dirty, dirty Mexican!”

And i said: “i’ll kick your ass, Dago bitch!”

tall for my race, strutted right past

black projects,

leather jacket, something sharp

in my pocket

to Pompeii School.

Get those Dago girls with teased-up hair

and Cadillacs,

Mafia-bought clothes,

sucking on summer Italian lemonades.

Boys with Sicilian curls got high

at Sheridan Park, mutilated a prostitute one night.

i scrawled in chalk all over sidewalks

MEXICAN POWER CON/SAFOS

crashed their dances,

get them broads, corner ‘em in the bathroom,

in the hallway, and their loudmouthed mamas

calling from the windows: “Roxanne!” “Antoinette!”

And when my height wouldn’t do

my mouth called their bluff:

“That’s right, honey, I’m Mexican!

Watchu gonna do about it?” Since they didn’t

want their hair or lipstick mussed they

shrugged their shoulders ‘til distance gave way: “

Dirty Mexican, dirty Mexican bitch.”

Made me book back, right up their faces,

“Watchu say?” And it started all over again . . .

What has happened is that Electra without her Toltec Agamemnon or his son has become Orestes herself—though she puts it in her own way. So in the next poem, “For Ray,” first, we see that he’s slid from Mexicano to Latino, with a strong tropical twist, like so many other gangueros who also held factory jobs (this is where Horowitz’s book is especially illuminating)—and she with him—the young kid playing the güiro at seven, then years later buying old records at the Old Town street fair, assigning the 1950s Pérez Prado Rey del Mambo trumpet stuff for Ray her Rey, but Cal Tjader’s afro-cuban jazz, and even soul sister Della Reese’s Cha Cha Cha stuff for herself—she, the scrawny scabby kneed kid who didn’t sing “Cielito Lindo” or “Cucurucucú Paloma” but was pleased to teach all who wanted how to dance, pleased to teach the he’s and she’s… but her final thoughts are still for her dad:

with timbales

and calloused hands

not from a career of

one night stands but the grave

yard shift on a drill press…

As with Bob Dylan’s song, “It’s all right” is the answer to a sense of anxiety, achieved here by partaking in the glide and slide of the “guacha guaro/guacha guaro” dance rhythms which seduce Electra into feeling that her father’s still alright, “still cool.”

The culminating Electra poem both confirming and problematizing Castillo’s Electra role is “Daddy with Chesterfields in a Rolled Up Sleeve.” This piece is too long and complex, and in some ways too confused or enigmatic for a full analysis here. It opens with the death of Doña Jovita (Granny), apparent paternal curandera grandmother of our Electra (by turns Ana/Ana María/Anita) and the effect of her death on the daughter’s dysfunctional extended family—but above all, on her, her mother and father. Primarily we focus on the question of the young daughter’s present and future. So her mother says:

“You’re like your father,

don’t like to work,

a daydreamer,

think someday you’ll be rich and famous,

an artist, who wastes her time

travelling,

wearing finery she can’t afford,

neglecting her children and her home!”

“The father lowers his eyes.” But the future artist/writer Elektra shouts out to Doña Jovita:

Don’t leave me behind with this mami

who goes off to work before light

leaves me a key, a quarter for lunch,

crackers for breakfast on my pillow

that rats get before i wake!

…Don’t leave me with this daddy,

smooth talkin’, marijuana smokin’,

mambo dancin’, jumpin’ jitterbug!”

Sure enough, Electra emerges celebrity artist and traveler, femme fatale to men and to women as well:

i speak English with a crooked smile,

say “man,” smoke cigarettes,

drink tequila, grab your eyes that dart

from me to tell you of my

trips to México.

i play down the elegant fingers,

hair that falls over an eye,

the silk dress accentuating breasts—

and fit the street jargon to my full lips,

try to catch those evasive eyes,

tell you of jive artists

where we heard hot salsa

at a local dive.

And so, i exist . . . .

Men try to get her eye, as she tells them “of politics, religion, the ghosts” she’s seen in Mexico and Chicago—and above all, of “the king [or rey] of timbales,”who is both Tito Puente and Ray himself, he of factory, gang and small time Chi-town Latin jam sessions. The men are intimidated and go away.

But women stay. Women like stories.

They like thin arms around their shoulders,

the smell of perfumed hair,

a flamboyant scarf around the neck

the reassuring voice that confirms their

cynicism about politics, religion and the glorious

history that slaughtered thousands of slaves.

Having conjured up Troy, the Aztecs, the Slave Trade, female abuse and so much more, now our Electra seeks to cure all by adding the shamanlike qualities she’s received from her supposed Guanajuato grandmother—qualities which, post-Gloria Anzaldúa but also post Agua como chocolate, she makes much of in her Xicanisma but are already here in this early poem and even reach out from here and elsewhere in My Father, to Peel My Love Like an Onion:

Because of the seductive aroma of mole

in my kitchen, and the mysterious preparation

of herbs, women tolerate my cigarette

and cognac breath, unmade bed,

and my inability to keep a budget—

in exchange for a promise,

an exotic trip,

a tango lesson,

an anecdote of the gypsy who stole

me away in Madrid.

So now, having projected much of world and personal history, Electra/Ana, etc. closes her poetic improve by taking us back to her working class Rey del Barrio, for a final riff which affirms much of what I’ve tried to suggest:

Oh Daddy, with the Chesterfields

rolled up in a sleeve,

you got a woman for a son.

All this said, and having tried to understand as much as I could, I find myself with a final doubt, a mystery I’ve previously cited above as an enigma which has haunted me for years and which I have never even dared to ask the poet even in her more mature years—all embodied in a few lines near but not at the end of the poem—as if intentionally somehow buried and de-emphasized amidst an array of distracting yet suspect iconic Mexican references:

The only woman who meant anything in his life.

—No creo que fue tu mama,—your wife whispers.

“I don’t care!” you reply.

—Que ni eres mexicano,—

“I don’t care!” you say for

doña Jovita,

la madre sagrada

su comal y molcajete,

la revolución de Benito Juárez y Pancho Villa,

Guanajuato, paper cuts, onyx, papier-mâché,

bullfighters’ pictures, and Aztec calendars.

What do these lines suggest?” Is all this so much prattle? Could this just be a spurned wife’s way of getting a little back at a man who placed her lower in his hierarchy of women than his perhaps mother/grandmother or how many other women? Is it that the mother just doubts or claims to doubt as a way of getting his goat? Or, could it be that Ray el Rey was not Mexican after all (we note he doesn’t deny his wife’s insinuation), that Doña Jovita, la madre sagrada was not his mother or grandmother, and if so, could it be that the Electra/Ana is not the daughter of a Mexicano and the grand-daughter or great granddaughter and blood-right heir of a Mexican curandera after all?

And what would that mean for our sense of Castillo’s identity, her work, and for the mixes that are part of Chicago Chicano literature and Chicano literature as a whole? Could he be Puerto Rican? Or even Italian? How does this matter cause us to re-think “The Toltec” or even the poet and girl persona in “Dirty Mexican”? Identity and identity politics seemingly so essential to so many poems here, and so many works of Chicano literature, may be based on a series of historical and cultural illusions with little basis in fact. But is whatever power we may find in this literature due to or in spite of its illusory essence of being?

∴

Marc Zimmerman. Emeritus, Latino and Latin American Studies, University of Illinois at Chicago, director Global CASA/LACASA Chicago Books. Commentator and contributor to El BeiSMan.