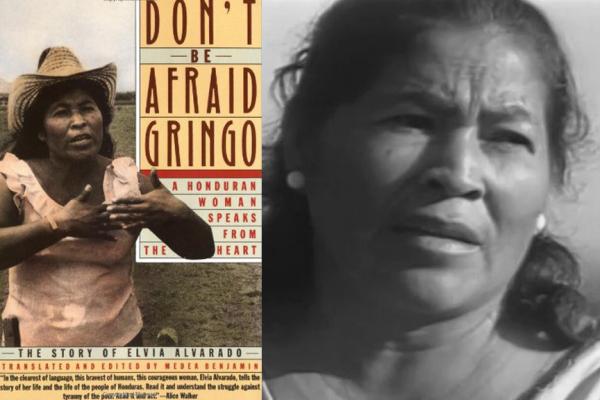

Don’t Be Afraid, Gringo

Don’t Be Afraid, Gringo: A Honduran Woman Speaks From The Heart: The Story of Elvia Alvarado

HarperPerennial, 1989, 208 pages, $9.69, ISBN-13: 978-0060972059

Elvia Alvarado’s memoir, Don’t Be Afraid, Gringo, tells her story of struggle, inequity, and perseverance as a Honduran campesina. Unfortunately, Alvarado’s fight seems to be in vain—as an individual, she is not likely to succeed in reducing the inequality present in her life. But her tireless work on behalf of campesinos all across Honduras does not go ignored. Her bravery and persistence has been instrumental in fueling the campesino struggle for justice, and has set an important precedent for all campesino activists that are presently fighting, and all campesino activists to come.

Throughout Alvarado’s career, there have been many hurdles and oppressors. The biggest of these is arguably the Honduran government. In its most basic form of subjugation, the government is quick to protect the rich in many capacities, but rarely do they help the campesinos. The government “doesn’t improve the clinics or open new ones in remote villages. It doesn’t check to see if our water is safe…The government only does things in the towns or the city, not in the remote areas where the people really need help” (25). Alvarado describes the dirt roads full of potholes in the campesinos’ villages, and how the government pours a truckload of dirt every four years for the presidential candidates’ cars—to “ask for their votes—not because they’re really concerned about improving the campesinos’ lives” (25).

But potentially their most harmful deed towards campesinos is failing to uphold the Agrarian Reform Law. The law states that land (state owned or privately owned) has to fulfill a social function and be completely used, otherwise it must be turned over to campesinos. Unfortunately, the National Agrarian Institute (INA) does not enforce the law the way it is supposed to. When campesinos send the INA a request for a staff member to evaluate a piece of land that is being used incorrectly, a lot of times, the staff member will be dishonest. They will take “a bribe from the landowner, and then make up a false report” (68). Even if their report ultimately says that the campesinos should have the land, the entire process takes years, and they have “never gotten land that way. The process just doesn’t work. Either the landowner pays everyone at INA off or the request gets bogged down in so much red tape that a decision is never made” (69).

A different hindrance—but arguably one that is just as powerful as the government (albeit in another capacity)—that Alvarado and other campesinas must overcome is the patriarchy; and the patriarchy is ever-prevalent in their society. Traditional gender roles are still customary, and women bear a lot of unnecessary burdens because of Honduran men’s machismo. Alvarado depicts a typical day in a Honduran woman’s life, beginning with waking up at dawn to grind corn and make tortillas from scratch, complete with washing clothes, ironing, cleaning, hiking to find wood and water, cooking, helping in the fields, and tending to the children (52). Because of men’s refusal to help with “women’s work” and because of men’s negative stigmas concerning assertive and organized women, campesina women are hesitant to get involved. They are afraid to speak out, and Alvarado confirms that “the hardest part about organizing women was that their husbands were so opposed. The men thought that organized women…would want to start bossing the men around. They said that men should tell women what to do, not the other way around” (88).

The United States is also a huge deterrent in Alvarado’s journey to equality. Firstly, their funneling of money into the Honduran government, as well as their construction of bases around Honduras serve to “strengthen the Honduran military, and that means more repression” for the campesinos (109). Additionally, American aid groups, who are very present in Honduras, are more of a hindrance than a help. Alvarado asserts that “Honduras is swamped by foreigners, most of them from the United States” (101). Alvarado points out several issues with voluntourists: “they’re here today and gone tomorrow…the programs they set up often fall apart when they leave…they insist on working with individuals instead of groups…they don’t bother to work with the structures we’re struggling so hard to set up” (103). Aid groups are ostensibly putting a Band-Aid on the problem, so to speak, instead of working to find a cure. They send food and clothes instead of going to the root of why Hondurans don’t have food and clothes in the first place. More than this, though, Alvarado points out that Peace Corps, and others alike are government organizations— “just part of the system that keeps us poor” (103).

The church also serves as an obstacle to Alvarado’s success, even if it did not start out that way. “When we started to walk ahead of them, they tried to stop us…the very same church that organized us, the same church that opened our eyes, suddenly began to criticize us, calling us communists and Marxists” (16-17). Not only did Alvarado’s church abandon her organization, priests elsewhere were discouraging and insensitive to campesinos’ conditions. “Rich priests…say the poor are poor because they were born poor. So that’s their lot in life…You must live your life as God gave it to you. You must live in your poor shacks, because that’s what God gave you” (31). Evangelical pastors are seemingly just indifferent to campesinos’ struggles. They “go around telling campesinos that the only thing that matters is the Lord…they shouldn’t take over the landowners’ land; they say it’s a sin to work with campesino groups” (32). Some campesinos became Evangelicals and left the campesino organizations, leaving Alvarado with less followers and an even more difficult time to accomplish her goal of reducing the inequality in her life.

This inequality is largely due to big landowners and foreign companies. They took land from the campesinos and have kept it, in violation of the law, because they can afford it. They “have money to bribe corrupt officials or fancy lawyers to forge their papers”, and thus, the power to remain in possession of their stolen land (69). (This seems reminiscent of what colonialism has established and what elites have maintained in the United States, for perspective). Furthermore, when the Agrarian Reform Law is upheld, landowners and the government are meant to give campesinos credit and technical assistance, which does not usually happen, sending campesinos into debt, and consequently, into a cycle of being cheated. Alvarado gives an example of a campesino group being cheated by a mine owner for four years, which does not seem to be totally uncommon, unfortunately. Landowners pay thugs to kill campesinos; campesinos are imprisoned, abused, and victimized (81).

But this persecution, among other aspects of the campesinos’ struggles, conversely seems to serve as motivation. Similarly, the machismo that deters campesinas, could be renamed as feminism, when seen as a tool of liberation. It, not unlike the campesinos’ persecution, drives them to keep fighting for their rights. They recognize and acknowledge men’s domination in their society, just like they recognize and acknowledge the landowners’ and government’s domination, and they do something about it. “But you should hear the organized women! Sometimes they talk even more than the men…The men are often afraid of the women organizing. Because once we’re organized, you can’t shut us up” (88).

Organization as a concept is also instrumental in Alvarado’s and campesinos’ journey towards liberty. Alvarado’s chapter “Organizing Bring Change” points out that once groups are organized, campesinos run them on their own; this facilitates the organization of more groups and pushes them further towards their goal.

Another force of liberation for Alvarado is the Catholic church; and largely, it is a force of liberation in a personal way. Throughout the book, Alvarado mentions her faith multiple times, and it becomes clear that Alvarado finds solace in her religion. But more than just serving as a personal refuge, the church enables Alvarado and campesinas through education. Alvarado proclaims that she had never been to a course before. “Most of us didn’t even know how to read and write. But the teachers…said it didn’t matter how much formal schooling we had…we were there to learn together” (12-13). Learning and getting educated was big for Alvarado’s end goal of lessening the inequality she saw, and that began in the church. Moreover, that course was the beginning of Alvarado’s social work with campesino organizations.

But as just one person who helped start this fight several decades ago, I cannot imagine her succeeding in reducing the inequality in her life. However, the work she does with these organizations is powerful and necessary. If she was not doing anything about these injustices, it is not hard to imagine that Honduran campesinos would be worse off. While Alvarado, as one woman, may not contribute much to the diminution of the inequality in Honduras—especially considering the fact that she has many more forces of oppression versus liberation (and the forces of oppression are indubitably powerful)—she has certainly paved the way for other campesino activists to make a change.

∴

Valentina Caballero is a freshman at The University of Oklahoma, where she is majoring in Elementary Education and minoring in International Development. Email: cabavalentina@gmail.com.